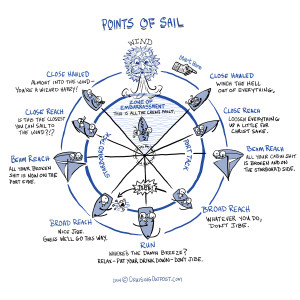

(For the non-sailor readers, there is a band around the direction of the wind in which sailing is not possible; that close to the wind the sails do not catch enough wind to propel the boat forward. If a sailboat points into this so-called “no-sail zone”, the sails will luff (i.e., flap around) and the boat will stall in irons (i.e., stop moving). The no-sail zone varies boat by boat. On the J24s we sailed at Manhattan Yacht Club, you could sail thirty degrees off the wind. Our tank Blue Moon sails at more like fifty degrees depending upon sea state. That’s nearly one-third of all possible sailing directions that are completely unsailable for us. The points of sail as you move out of the no-sail zone are, in order, close hauled, close reach, beam reach, broad reach, run and dead down wind.)

(For the non-sailor readers, there is a band around the direction of the wind in which sailing is not possible; that close to the wind the sails do not catch enough wind to propel the boat forward. If a sailboat points into this so-called “no-sail zone”, the sails will luff (i.e., flap around) and the boat will stall in irons (i.e., stop moving). The no-sail zone varies boat by boat. On the J24s we sailed at Manhattan Yacht Club, you could sail thirty degrees off the wind. Our tank Blue Moon sails at more like fifty degrees depending upon sea state. That’s nearly one-third of all possible sailing directions that are completely unsailable for us. The points of sail as you move out of the no-sail zone are, in order, close hauled, close reach, beam reach, broad reach, run and dead down wind.)

The weathervane is hovering as close to dead-into-the-wind as it can without the sails luffing. The wind is rushing over the bow, down the deck, and smacking the crew across the face. If it’s raining and cold, that can be quite a smack. The sails are trimmed tightly, tell tales streaming, jib and main sheets winched in taught, Dacron screaming under the pressure. The boat is heeled over, leeward toe rail skimming the surface of the water, crew hiked out over windward rail. Close hauled. It’s intense! I love it!

Close hauled was always my favorite point of sail. It is the most exhilarating point of sail, with the apparent wind ramping up considerably higher than the true wind and the boat heeled over teetering on its toe rail. It is also the point of sail on which the physics of sailing is easiest to understand and most apparent, the sails quickly luffing if you round up into the wind, the weather helm pulling on the helm. It is the point of sail when you are most closely helming, always trying to come up into the wind a bit more, falling off as the sails luff, playing that groove over and over again to maximize speed and angle. (Racers have now stopped reading, knowing that sailing deep downwind with a spinnaker up requires the much closer helming than close hauled, but we don’t have a spinnaker on Blue Moon and I don’t race.) This point of sail makes sense; the helm and sails speak to me. It just feels fast; it feels powerful. My feet are braced, my hair is streaming behind me and I have a huge smile on my face. I am an eight year old at the helm of a Sunfish again.

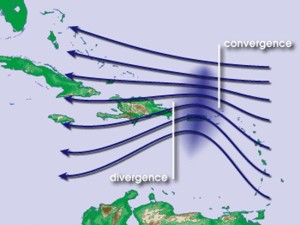

Close hauled was my favorite point of sail until we set off down the Thorny Path. For centuries, wise old salty sailors forewent the eight-hundred-nautical-mile-or-so sail from the Bahamas to the Caribbean, referred as the Thorny Path. The easterly trade winds in those latitudes are relentless; they will blow between fifteen and twenty five knots from a compass direction of between seventy and one hundred and ten degrees, all day, every day. Without a motor to power into the wind, no sailor would be so arrogant as to think he could sail into such wind for such a long stretch. It’s not just thorny, it’s contrary to the laws of physics and the nature of weather. Unless the prevailing winds clock or back a bit, you cannot sail from the Bahamas to the Caribbean, no matter how closely you haul in your sails and how high on the wind you point.

Along comes the diesel engine, and suddenly sailors are traveling down the Thorny Path, motorsailing as close to the wind as they can – motor-assisted closed-hauled sailing you might call it. Bruce VanSant did it repeatedly for several decades and wrote a book extolling a “Thornless Path” that takes advantage of favorable winds and coastal currents. Weather router Chris Parker mentions the westerly eddies off the northern coast of the Dominican Republic and the southern coast of Puerto Rico. We followed their advice (mostly). We hauled the sails in close; we fired up the engine. We hugged the coast through the midnight hours when the coast may generate some westerly winds. We waited out gale force winds directly out of the east, and jumped on any abatement or clocking or backing in the wind. It was not thornless; thorny is a gross understatement.

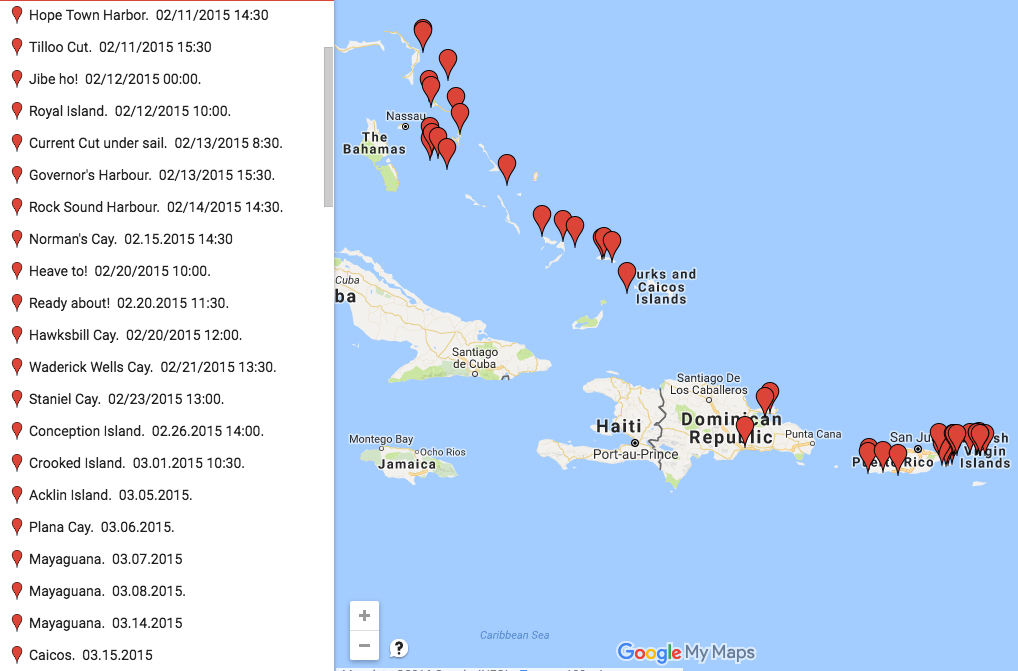

We left the Abaco Islands in the northern Bahamas (i.e., northwest of the Caribbean) on February 11, 2015. We were headed to Grenada (i.e., southeast of the Caribbean) by June 1, 2015. Perhaps we were naïve, or poorly informed, or just brash New Yorkers who think nothing is impossible. From February 11th in Hope Town until April 7th in St Thomas, we felt nearly every thorn of the Thorny Path. We consistently beat into the wind, diesel engine roaring, sails close hauled, waves bashing our bow, water flooding down our decks, sails tearing and fraying, boat heeled over hard and all of our worldly possessions in the cabin teetering on end. If the wind was strong, the waves were big and the current was against us, we might not make more than a knot or two. Because we’re a heavy boat with a full keel, every third or so wave might hit us just enough to slow our speed by a knot or two. So when you’re struggling to make two or three knots, and a wave slows you by a knot or two, you’re dead in the water until the boat can gain a little momentum back. That’s pretty thorny.

One night on the southern coast of Puerto Rico, exhausted from over a month of beating into it and rushing to get to St Thomas to meet friends, we made the poorly-thought-through decision to shut down the engine and just sail as close hauled as we could for the better part of a day, hoping that when we tacked back toward the island we would make some headway. It was a quintessential close hauled sail – heeled over, bashing waves, wind roaring down the deck. We were shifting watches when we tacked; when I saw on the chartplotter that we were headed back essentially right where we’d come from, after what had been a stressful, intense day-long sail closed hauled in big winds and big seas, I was so deflated all I could do was sulk down the stairs and fall into a deep sleep, pfd around my neck, headlamp on my forehead. We travelled nearly two hundred nautical miles over twenty-eight hours and made only twenty nautical miles in the direction we needed to travel. That’s not thorny; that’s soul crushing. It very quickly made close hauled my least favorite point of sail.

Nearly all of the islands and anchorages between Staniel Cay in the Exumas and Vieques in the Spanish Virgins Islands are a complete blur to me. We usually stayed for no more than twenty-four hours, once staying only seven hours to sleep and regroup (ironically, on the Isla Caja de los Muertos (Coffin Island)). If we went to land, it was solely to buy some food and thank God for a little tierra firma under our feet. Conception Island had a terrible swell that made sleep difficult. Crooked Island had no eggs for sale for the few days we were stuck there, and Mayaguana Island had no beer for sale for the seven days we were stuck there. We went to land on the southern shore of Puerto Rico for a quick dinner before setting off again at sunset that night; the sandy beach, crystal blue pool and restaurant with plentiful food and drink looked like an oasis in the desert. We ate our meal in complete silence. I’m sure the staff and other diners thought we were zombies. Our eyes were so blurred from weeks sailing closed hauled.

The only thornless passage of the two months from the Abacos to St Thomas was the Mona Passage. The eighty-mile Mona Passage between the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico is infamous for being a long treacherous stretch of water. In addition to the strong trade winds funneling off of mountainous Puerto Rico and the tidal currents swirling off both Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, the entire force of the Atlantic Ocean builds and builds as the depth of the water skyrockets from 28,000 feet in the Puerto Rico Trench of the Caribbean Sea to less than 1,000 feet in the Mona Passage. Internal tidal waves can be as high as one hundred and twenty feet. Professional captains on strong, fast boats have set out from the Dominican Republic and turned back defeated and broken after days of beating into it. The Mona Passage is purportedly not very mona (pretty) at all. We waited in Samana, DR until the winds abated, and had a glorious Mona crossing. We motorsailed closed hauled for thirty-seven hours in calm seas, with dolphins by our side. As we neared Puerto Rico on my last night watch of the passage, the seas were so becalmed that the stars were reflected in the water. That’s about as mona as it gets in my book.

In retrospect, we should have delivered the boat from New York directly to St Thomas and skipped the close-hauled sail down the thorns completely. (Jason says, “I thought you loved being close hauled. I would have delivered the boat to the beamy waters of the Eastern Caribbean if I’d known you didn’t like it anymore.”) But we’re probably better sailors and navigators having sailed it and we’re definitely a stronger couple having survived it. It also makes us appreciate the beam reach sailing of the Eastern Caribbean and the downwind sailing to the Western Caribbean that much more. (Stay tuned for blogs on those points of sail coming soon!)

Sail ho!