Published October 2016, Sail Magazine

Published October 2016, Sail Magazine

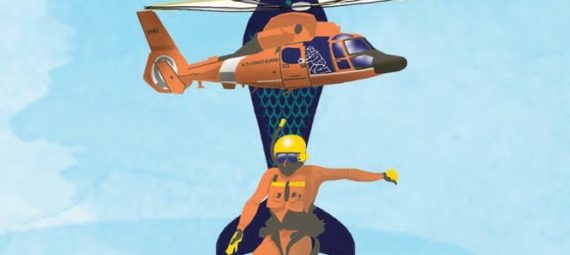

“My name is Petty Officer Jaime Vanacore. I am your rescue swimmer.”

Her Dolphin helicopter hovering 70ft over the peaks of the waves, Jaime had zipped down from the helicopter to the ocean, first with 25 knots of wind whisking her around and then with 15ft waves smacking her. She had unclipped from the line and fallen the last 10ft into the trough of a wave. After that, she had swum the last 30ft to the life ring dragging behind the boat. Hand over hand, she had pulled herself along the life ring’s line some 75ft to the back of the boat through the waves. She then hoisted herself from the water onto the stern of the boat. She was completely unfazed, without a drop of sweat or a belabored breath. The boat’s crew was winded just watching her.

The Island Packet 380, Blue Moon, had set sail from Marsh Harbour in the Bahamas on April 23, 2014, headed for New York, with a crew of four middle-aged men. They were all veteran sailors with significant delivery experience in the Atlantic. On this delivery, they had also already survived three significant inconveniences—a bout of food poisoning, the head clogged beyond repair or use, and the stove’s solenoid fried and unreachable in the rough seas—nonetheless, they believed they could make it the last 100 miles to New York without further incident.

Six days later, after rounding Cape Hatteras, they had been heeled over hard for 48 hours, pounding into the oncoming seas, pummeled by gale-force winds out of the northeast. Waves were crashing over the bow and into the cockpit, and the 30-plus knots of wind pelted the crew with cold horizontal rain. Standing watch had become very uncomfortable, and resting in the saloon had become nearly impossible, as the crew shivered in water-drenched foul weather gear. The wind and rain were forecast to last for another day, and the air and sea would just keep getting colder the further north they sailed. Nightfall was coming and would drop the temperature even more for a few hours. There was no hot meal to warm them. They were beaten up, but sailing on.

The crew was changing watches at around 2000. First mate James was preparing supper in the galley. Thomas was in the saloon, preparing to start his shift with James. He stood for a moment, his back against the bulkhead, to pull up his foulie bibs. The boat fell out from under him and yawed hard. Thomas’s hand reached for the bulkhead and slipped. His feet struggled to reconnect with the floor but got tangled in his bibs. As his body lurched forward, his forehead, just above his right eyebrow, connected with the lip of the shelf behind the port saloon settee.

A loud crunching noise was followed by near silence. Blood started gushing over the shelf, the seats, the salon floor and Thomas’s face. A slice of the shelf tumbled to the ground and slid around on the damp floor. The skipper, Jason, scurried down the companionway from the cockpit to see what had happened. James started searching for ice and a wet towel. Robert stayed at the helm, guiding the boat through the careening waves. Thomas sat down, silent, holding his forehead.

“How do I look, Captain?” Thomas asked when Jason bandaged him up and assessed his mental state. He would accept the diagnosis and serve the orders, regardless of how he really felt. He was a trouper—a trouper who could keep sailing through the gale with a possible concussion.

Short on crew after an arduous six-day voyage, at least six hours from the closest port of call and approaching nightfall, Jason hesitated for a second before hailing the Coast Guard on the single sideband radio. The gauze on Thomas’s head was turning red, and the bleeding showed no signs of abating. Jason could suture the wound or patch it up with duct tape, but it would likely leave a nasty scar that would require plastic surgery to correct. Jason also wanted to be able to direct his attention to getting the rest of the crew and the boat through the storm and back to land safely. With medical attention within reach and a tough sail ahead, the only answer was to let the professionals do their respective jobs.

“Pan-Pan Pan-Pan Pan-Pan. Atlantic City Coast Guard, this is the sailing vessel Blue Moon.” Static.

“Pan-Pan Pan-Pan Pan-Pan. Atlantic City Coast Guard, this is the sailing vessel Blue Moon.” Static.

The Coast Guard was not responding to the radio, because (as the crew would later learn) the Coast Guard had stopped monitoring frequency 2182 kHz. Jason grabbed the satellite phone, a means of communication that had at first seemed superfluous but now seemed invaluable, and went out to the cockpit to make the call.

“This is the sailing vessel Blue Moon. Location is 38 degrees, 38 minutes North, 074 degrees, 7 minutes West. I have a crew in need of immediate medical attention.”

The call lasted a few minutes, with the Coast Guard requesting the crew to change course toward the Coast Guard’s station in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Blue Moon fell off and sailed due west for about 40 minutes, waves crashing over the beam, before hearing the Coast Guard helicopter nearing. As the helicopter hovered close over the stern, the Coast Guard hailed the boat on the radio and instructed the crew to lower the sails, turn the engine on and throw the life ring off the stern with a long line. Because of the mast, standing rigging and the sea state, the basket could not be dropped on the boat’s deck. The Coast Guard rescue swimmer and Thomas would have to jump into the water.

Once on board, the rescue swimmer ambled through the cockpit and down the companionway, leaving sheets of seawater behind her. She inspected Thomas’s wound with a flashlight.

“I can tape you up with duct tape, or you can come with me. If you stay, you’ll have a nasty scar. If you come, you’ll have to jump in the water in your foulies. It’s up to you.”

Thomas conferred with Jason and James, and both agreed that the bad scar and difficult voyage should be avoided if possible. Jason and James helped Thomas pack a dry bag with his wallet and his cell phone and Thomas joined the rescue swimmer in the cockpit.

“As soon as my feet hit the water, you need to jump off the stern too. If you hesitate, there will be too much distance between us in the water, and I may not be able to get you into the basket,” Jaime explained to Thomas.

“Don’t worry,” Jason joked. “I’ll push him if he doesn’t jump.”

Thomas jumped as soon as Jaime’s feet left the swim platform, well before she hit the water. She then pulled Thomas away from the boat and, keeping his back toward the oncoming waves, helped him into the basket that the helicopter had dropped into the water. The short time in the frigid water seemed like forever, as Thomas focused on his breathing to remain calm. After he was lifted out of the water and into the helicopter, the basket dropped again and Jamie was lifted up. Our crew all waved as the helicopter pulled away, in awe of the tremendous skill and courage of the pilot and rescue swimmer.

During the 20-minute flight to the Coast Guard base at the Atlantic City Air Station, the crew gave Thomas a blanket, gloves and a hat, and helped him peel off his wet clothes. When they landed, an ambulance was waiting to take Thomas to a local Atlantic City hospital. There, he was admitted, analyzed and sewn up with 14 stitches in short order, after which he took a taxi to the bus station. Traveling that fast, after a week of sailing at 5 knots, was dizzying.

Thomas looked like a mental institution escapee in his scrub pants, hospital gowns, sailing boots and foulie jacket with a compression bandage on his forehead and a bright orange PFD in his hand. It was the middle of the night at a bus station in a town full of questionable characters. Sensing that something was awry, the bus ticket agent initially refused to sell Thomas a ticket. After he agreed to keep his foulie jacket on for the duration of the bus ride, the ticket agent sold Thomas a ticket for the 0530 bus to New York’s Penn Station.

It was a long voyage home from the Bahamas for Thomas: a sail, a swim, a frogger basket ride, a helicopter ride, an ambulance ride, a taxi ride, a bus ride and a subway ride —and all but the first part while dressed in scrubs and foulies, with a bandage over his forehead and an orange lifejacket around his neck. The crew still talks about the mermaid who boarded Blue Moon and took Thomas out to sea.

What they learned

• One hand for you, one for the boat. Especially when you’re tired.

• Keep redundant forms of communication. Satellite phones are becoming an invaluable tool on board.

• Double-check emergency radio frequencies and phone numbers before every sail.

• Call for assistance as soon as you think you need it. Assistance is not immediate.

Brita Siepker lives aboard Blue Moon, an Island Packet 380, cruising the Caribbean. You can follow her travels on her blog, sailho.com.

Wow! Beautiful article!

What a nail biting experience. Great article with valuable lessons

You were on the Blue Moon at this time?

Did Thomas have to reimburse the Coast Guard for the helicopter rescue?

What are foulies?