Lombrices (worms), correcaminos (scabies), piojos (lice), pulgas (flees), piedras de la vesícula biliar (gallbladder stones), and parásitos and tuberculosis (thank goodness for cognates). I lived several years in Latin America, I negotiated multi-billion dollar transactions in Spanish for the better part of a decade, and I generally consider myself fluent, but I was beyond my paygrade volunteering as a Spanish-English translator with Floating Doctors at their medical clinics.

Lombrices (worms), correcaminos (scabies), piojos (lice), pulgas (flees), piedras de la vesícula biliar (gallbladder stones), and parásitos and tuberculosis (thank goodness for cognates). I lived several years in Latin America, I negotiated multi-billion dollar transactions in Spanish for the better part of a decade, and I generally consider myself fluent, but I was beyond my paygrade volunteering as a Spanish-English translator with Floating Doctors at their medical clinics.

Floating Doctors is a US non-for-profit that provides free health care services and delivers donated medical supplies to remote Ngäbe indigenous communities in and near the archipelago of Bocas del Toro, Panama. Every week, they dispatch a cadre of medical volunteers in a cayuco (somewhere between a canoe and a Thai long-tail boat, dug out of a single tree trunk with an outboard engine on the transom) to villages deep in the Panamanian jungle. In the four weeks that I volunteered with them, we visited seven villages, including four days and three nights at one of the larger, more remote villages, and attended to nearly a thousand patients.

Few of the Floating Doctor medical volunteers speak Spanish, and few of the Ngäbe speak English, so Spanish-English translators are the necessary link between doctor and patient. Sometimes, Ngäbere-Spanish translators are needed as well, especially for the older patients who were never educated in Spanish. Sound like a game of telephone with delicate matters lost in translation?! Some of the patients from really remote locations stared blankly at us and didn’t answer simple questions. Others answered two completely contradictory questions with the same answer: “Is it feeling better now?” “Yes.” “Is it worse now?” “Yes.” Luckily, the medical providers were dedicated to providing the best level of care possible, even if that meant rehashing over and over again until the symptoms made sense and a diagnosis was possible.

Within minutes of arriving to our first clinic in Valle Escondido, I was pretty sure I had contracted all these yet-untranslatable maladies from the children climbing in my lap, clutching my hands and coughing in my face. (I was also pretty sure there was no way Jason was letting me back on the boat carrying all those bugs, bacteria and viruses from the jungle.) But when a nine-year-old girl suspected to have tuberculosis wants to sit on your lap and curl your hair around her finger while the doctors poke and prod her delicate body, the last thing on your mind is what kind of germs you may be catching. When a six-year-old boy with open wounds all over his head and body from scabies just wants to roll around in your lap like you’re a beanbag chair, you don’t get squeamish or nervous or disgusted. You try to be as stoically resilient and warmly friendly and blindly trusting as they are.

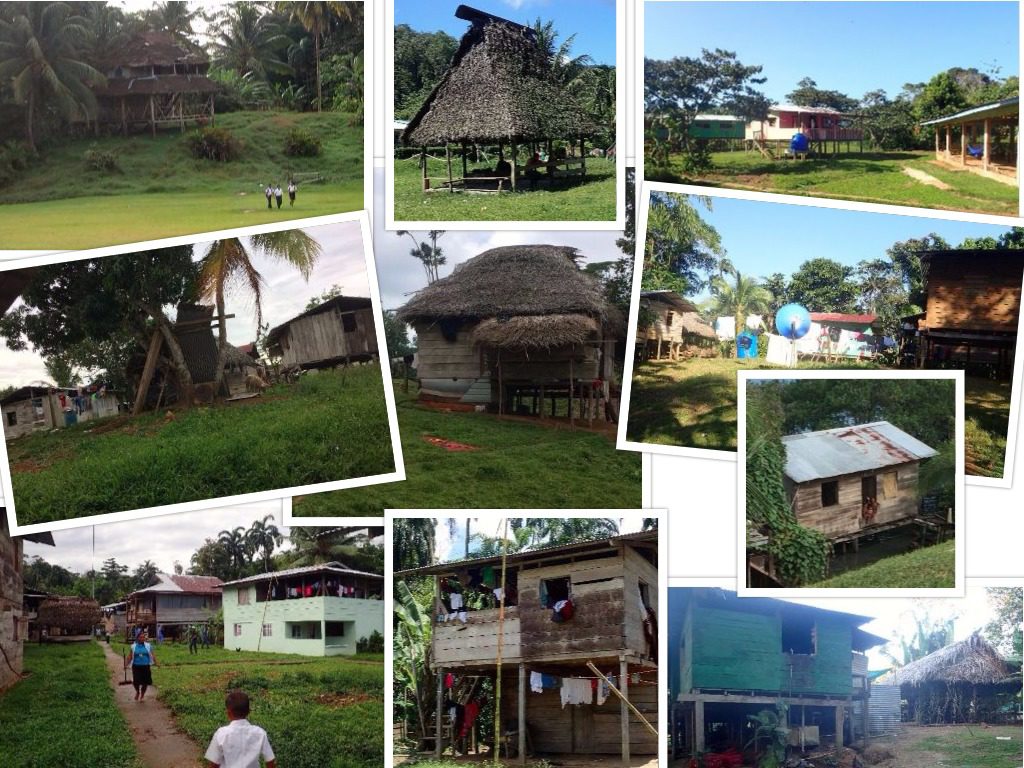

The Ngäbe are ranked as one of the poorest indigenous communities in Latin America and as the poorest community in Panama. Government statistics estimate that 90% of the population lives below the poverty line, and the villages we visited confirmed the stats. The Ngäbe survive on subsistence farming, and whatever small income can be garnered selling excess food to stores and handicrafts to tourists when they can get out of their village. They live with very limited solar-panel electricity, very limited clean water sources (usually rainwater, and Bocas is prone to long dry spells), no sewage management (usually a wooden shack over the estuary with a missing slat in the floor) and very limited food sources (best I can tell they eat a lot of plantains, rice and beans and drink a lot of hot chocolate and milky oatmeal).

They live in wooden huts raised off the ground with dirt floors and a tin roof; they sleep in hammocks and cook over a fire pit. Basic hygiene skills are lacking, reliance on “botanical” remedies is prevalent, dehydration is chronic and malnutrition is not uncommon. One community we visited lived in what I can only describe as urban squalor, with garbage strewn all over the village and human feces floating in the river. And there is essentially no way out – the waterfront villages have no road access and boat service out of town is prohibitively expensive.

The most frequent diagnoses were stomach worms, parasites, scabies, fungal infections, viral infections and bacterial infections, together with chronic aches and pains from a lifetime of tough physical labor. Some of the more dire diagnoses – advanced kidney failure, hernias, heart murmurs, tuberculosis, gall stones – require referral to experts in the closest city (a boat ride plus a long bus ride away, often paid for and organized by Floating Doctors). Some patients walk hours to get to the clinic, and all wait months between clinics for their near-only access to medical care. The women come toting their army of children with runny noses, pussing bug bites and distended stomachs; sometimes they ask us to accompany them home to attend to their invalid parents. The men appear to avoid the clinic unless they’re really sick; after a few clinics where men stood just outside the clinic looking in, we theorized that they were watching to see who received the birth control injection that Floating Doctors offers.

A seventy-six-year-old man complained that his knees hurt when he walked for a couple of hours in the mountains; he laughed out loud and praised God when we told him it was a miracle he’s still walking in the mountains at his age. Women bear children as early as fourteen, and may have upwards of eight children; the 35+-year-old pregnant women looked much more like grandmas – wrinkled and hunched over – than glowing expectant mothers. Most women suffered from neck and back pain from carrying heavy loads of yucca, firewood and children across their forehead and shoulders for several hours a day in kra. We walked through knee-deep mud and shimmied under barbed-wire fence to visit the home of a woman who didn’t know her age and could no longer walk; she seemed quite dubious of the three blonde girls doling out free medical advice but promised to take her blood pressure pills and use her inhaler.

Despite all that – the poverty, the physical labor, the chronic maladies – the Ngäbe people were some of the happiest I’ve met in all my world travels. Man, can they smile, can they laugh, and can they take delight in the simplest things. Smiley balloons made out of latex gloves can entertain a group of kids for hours; pictures and music on my cellphone could captivate them for days. Even as they are suffering from serious illness they maintain a straight back and a wide smile. On our second day, a Ngäbere speaking grandmother kept jabbering away at me in Ngäbere and laughing because I couldn’t understand her. One of the women who cooked for us on our multi-day clinic laughed a full belly laugh after our four sentence conversation, repeated every time I went into the cooking hut, in Ngäbere (the only sentences I learned): “Ñantörö!” “Ñantörö!” “Tikä Brita.” “Tikä Magdalena.” Hello! My name is….

Despite all that – the poverty, the physical labor, the chronic maladies – the Ngäbe people were some of the happiest I’ve met in all my world travels. Man, can they smile, can they laugh, and can they take delight in the simplest things. Smiley balloons made out of latex gloves can entertain a group of kids for hours; pictures and music on my cellphone could captivate them for days. Even as they are suffering from serious illness they maintain a straight back and a wide smile. On our second day, a Ngäbere speaking grandmother kept jabbering away at me in Ngäbere and laughing because I couldn’t understand her. One of the women who cooked for us on our multi-day clinic laughed a full belly laugh after our four sentence conversation, repeated every time I went into the cooking hut, in Ngäbere (the only sentences I learned): “Ñantörö!” “Ñantörö!” “Tikä Brita.” “Tikä Magdalena.” Hello! My name is….

Spending time with the Ngäbe was a welcome reminder that life can be full in the absence of the creature comforts and consumer excesses we’ve all gotten so used to. It was also rewarding to see how a few dedicated people and some key resources can make a fundamental difference in the lives of others. These were not the kind of lessons I learned in ivy league towers or New York boardrooms. Getting out of the city and out into the world for the last two and a half years has continued to open my eyes and heart to how the rest of the world lives. We hope to be blessed with many more experiences like this one.

Every time I hear from you (even though I seldom communicate back) I love you more. You are truly living life and, of course, enriching everyone on the way. I know you didn’t post this to receive praise, I am just truly amazed at the life you have chosen to live.