After my father introduces me as his “homeless daughter,” he loves to tell people that I *hated* sailing as a kid.

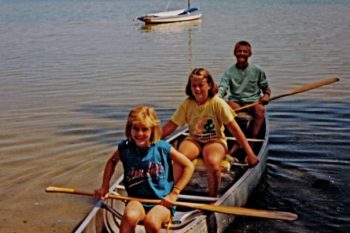

Summer mornings, my mother dragged me out of bed to go to sailing lessons at the Glen Lake Yacht Club. Sailing was the last thing I wanted to do; the water was cold, the wind was fluky, and (mostly) I’d rather be waterskiing. Any time on the slow Sunfish sailboat meant less time behind the fast Supra ski boat. I had my priorities.

|

|

We spent the chilly mornings of June in the yacht club’s clubhouse, gathered around a chalkboard, learning sailing’s terminology and technicalities. We memorized points of sail and rules of the road. We recited the parts of the boat and each of their functions: halyard to hoist the mainsail, tiller to control the rudder, rudder to change the direction of the boat, daggerboard to stop sideward slide. I mastered the words and ideas, but dreaded getting out on the sailboat. Was I scared of failure? A sailing instructor from later in my life likes to say, “Illiterate Vikings have been doing this for centuries; you can do it.” No one else at the club failed to learn; I couldn’t be the first.

And then one July morning in 1987, the yacht club’s kids’ director Bob Sutherland towed my Sunfish to the middle of the lake, turtled it and left me behind to sail it back to the yacht club. Bob let my older brother and his friends – Pete Warburton, Chuck Crawzack, Jeff Cook – pick me up and carry me down the dock and onto the pontoon boat, kicking and screaming and threatening to tell my mom and all of theirs. They all learned to sail without such drastic measures; they all raced in the weekend regattas, displayed medals and trophies to prove their worth. I would have to unturtle my sunfish and sail it back to the dock to prove mine.

At that early hour in the morning, the sun would have been just breaking over Miller Hill, leaving a long trail of sparkling water across the lake before it. The wind would have come out of the west, blowing from Canada down to Wisconsin, across Lake Michigan, tumbling down the crest of Alligator Hill right into Glen Lake. The ripples in the water Bob taught us to look for would have told me when to trim and when to ease, the telltales on the sail telling me when to fall off and when to come up. I would have been cinched in tight in my favorite hot pink life jacket, stark tan line across my back from where the life jacket ended to where the bikini bottom started.

I know I did manage to sail back that day, but I don’t remember if it required several tows out and back, or coaching along the way, or some bribe by Bob or my parents. All I can tell you is that on that day, aboard that boat, in that lake, I learned to sail. I didn’t learn to love to sail that day, that took decades.

I know I did manage to sail back that day, but I don’t remember if it required several tows out and back, or coaching along the way, or some bribe by Bob or my parents. All I can tell you is that on that day, aboard that boat, in that lake, I learned to sail. I didn’t learn to love to sail that day, that took decades.

***

I started sailing again two decades later, after watching the Manhattan Sailing Club boats zip back and forth across the Hudson River. I’d been grounded for over a decade – first traipsing around Latin America and then pounding the streets of Manhattan. I moved to Tribeca in downtown Manhattan because I thought I’d like the views of the Hudson River. Views are never enough for a true water baby; you’ve got to get in it, even if it is a cesspool heavily laced with PCBs from industrial plants up river and drowned in untreated sewage dumped from the city every time it rains. Dead rats float in the marina, the health department warns not to eat anything fished out of it, and a putrid smell of marine decomposition wafts up over the city, rivaled only by cat-urine-drenched asphalt alleyways on a blazing hot summer day. I spent hours gazing out at the Superfund-fed Hudson River, gearing up for the first plunge.

When the only water a stone’s throw away is a cesspool, you get in the cesspool. And by get in it, I mean swim, dinghy sail, kayak and waterski in it, and then hose down with bleach and rinse your mouth out with Scope. My mother pleaded with me to wear my swimming goggles when I started waterskiing on the Hudson near Midtown Manhattan.

When I joined Manhattan Sailing Club in 2012, the sailboats were just the easiest means to get out on the water regularly. I thought that a twenty-four foot sailboat in a river would allow me to be very close to the water without actually breaking the surface of the cesspool. Luckily I quickly met a guy with a bigger sailboat that kept me several feet out of the cesspool and swept me out to the (slightly cleaner) waters of the Long Island Sound and the Jersey Shore on the weekends, and a new appreciation for sailing was born. Sail ho!

***

That makes me just about the most unlikely cruiser. I didn’t (and still don’t) love the sport of sailing. I didn’t dream about living on a sailboat before moving aboard. I didn’t read books and blogs about cruising. I didn’t research boats and destinations. I didn’t even complete the requisite sailing classes before embarking. I jumped into this new lifestyle as a cruiser headfirst, eyes closed, nose plugged.

I knew that, no matter what the sky, the sea or the boat could throw at me, life is better on the water. And a sailboat is just a sustainable way to live in, and travel by, water.

You’re not enthralled with sailing per se. You’re enthralled with living on the water under a sail, moving among gorgeous islands and meeting fellow cruisers in exotic harbors.

As long as I’m on water I can swim in, I’m happy.

Great story!

Good stories! Did you ever read the book Love with a Chance of Drowning? Great story about a couple on a boat…it is a lot of hard work, but what beautiful places you must visit.