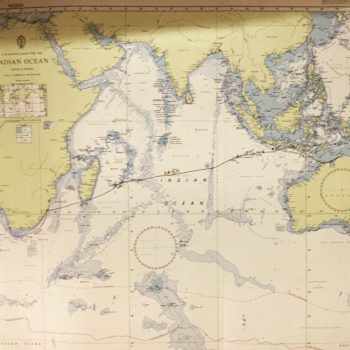

I crossed the Indian Ocean under sail: nearly 7,000nm/8,000mi/13,000km, just under three months shore to shore, 47 days underway, stopping in Indonesia, Christmas and Cocos Keeling Islands, Mauritius, Reunion and South Africa. We entered the Indian Ocean on 04 September 2018 from Darwin Australia, and exited it on 27 November 2018 at Cape Agulhas off the coast of South Africa.

For a girl born and raised on the shores of the Great Lakes, the Indian Ocean is a world away. The Atlantic I’d sailed; the Pacific I’d swum; but the Indian I’d seen only once before setting sail across it in September.

After the earthquake and tsunami in Japan in March 2011, I took refuge in a resort on the eastern shore of the Andaman Sea in Phuket, Thailand. It was my first sight of the Indian Ocean, and I was wary of water. It took me a day or two to walk down the dune to the water, and another day or two to walk into the water. This water that I had so loved – that I relied on to keep me centered and grounded – had caused mass destruction and killed tens of thousands of people. It had bent steel and dissolved concrete. This force that usually empowers us and transports us had brought its entire strength down on us. It crippled Japan. It broke my heart. And yet, there, in the Indian Ocean, it was the same soothing sound of waves breaking on the sand that had lulled me to sleep in the Great Lakes all those years. Finally, I laid down in the surf and let the water wash away my tears, let the waves relax my body. I made my peace with the ocean.

When I said goodbye to the Pacific Ocean at Manly Beach in Australia in August, I promised the Pacific that I would always love it, that it would always be my first, but that it might not always be my favorite. I knew I would love the Indian Ocean the most. The Indian Ocean is epic – not the biggest, widest or deepest – but the Indian Ocean would undoubtedly be the most challenging. Bernard Moitessier called the Indian Ocean “the most savage of the three,” and my friend Peter eloquently said, “These seas ain’t for sissies.” It promised to most test my mettle; I like to test my mettle.

| Pacific Ocean | Indian Ocean | Atlantic Ocean |

|

|

|

The Indian Ocean has packed the strongest wind and the biggest seas I’ve seen so far in the first 16,000 nautical miles of my circumnavigation. On the 2400nm passage from Cocos Keeling to Mauritius, we had sustained winds of well over 20 knots for five days straight, gusting into the 30s, and on the 900nm passage from Richards Bay to Cape Town in South Africa, we had gusts up to 40 knots for a few hours. (In both cases, other rally boats within sight of us reported much stronger winds, so either Blue Pearl’s wind instruments are not very precise, we have been very lucky, or others exaggerate.) Seas in the Indian Ocean have often been over 2 meters, and have topped out somewhere between 4 and 5 meters. (I admit I am not particularly good at estimating wave height, so I tend to guess low.) We rarely saw much more than a meter or two seas in the Pacific, and only a couple of times saw 25 knots of wind or more.

|

|

|

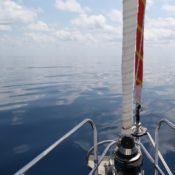

A Rare Calm in the Indian Ocean, Australia to Indonesia

The Indian Ocean has also proved the trickiest in terms of weather routing and navigational planning. Most boats in the rally relied on advice from professional weather routers, and gathered regularly before each passage to share information and plan routes.

On the passage from Reunion to Richards Bay, the wind and the current varied drastically and quickly; we planned a series of waypoints that we thought would provide the best combination of manageable winds and favorable current, and often found ourselves facing adverse current or stuck in doldrums. The wind went from under 5 knots from behind to over 25 knots on our nose in an instant, and current went from a knot or two of favorable current to a knot or two of adverse current inexplicably in the middle of the sea.

On the passage from Richards Bay to Cape Town, we found favorable current where we’d been advised to expect adverse current, and adverse current along the famous 200 meter contour where all sources say the best current is. The professional weather routers and local experts all agreed that a 900nm straight shot from Richards Bay to Cape Town without stopping was, generally, not possible because of the short weather windows and, in our specific window, not advisable because of strong southwesterly winds kicking up around the cape.

As Moitessier wrote fifty years ago, the western waters of the Indian Ocean are “the dangerous meeting ground of warm and cold currents, which can raise a monstrous sea (the word is not too strong)” [emphasis in original] and “the most dangerous . . ., where frequent gales raise an enormous sea . . . .” The seas were big, the winds gale force, and the current fast; we were double handing for 108 hours over 900 miles; we were beat tired by the time we pulled into Cape Town. It’s not surprising we were most tested in these waters.

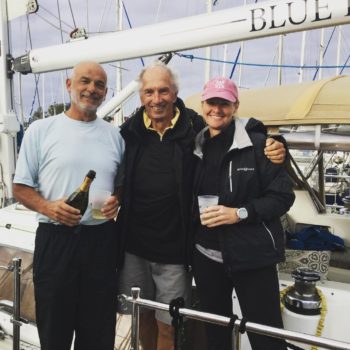

We were very fortunate. Blue Pearl is a tank, and handled the strong wind and big seas like a pro. Captain Ruud is confident and conservative, and brought us across safely. Boats around us faced much worse conditions. A former Amara and Blue Pearl crew member suffered head trauma on the Cocos to Mauritius leg and was evacuated in high seas by a coast guard vessel and rushed to the ICU; Karen is recovering well in the UK and plans to rejoin the rally. A fleet of Oyster boats that we have been following around got beat up on the Reunion to South Africa leg and had to bail out in Madagascar just a week ahead of us. On the passage to Cape Town, friends reported facing twice as much wind as forecasted and seas you couldn’t make headway in.

I know I’ll sail the Indian Ocean again, hopefully on the northern route, but for these 44 days on land in Africa before we cross the Atlantic, I am very thankful to be done with her for a while. Till we meet again, my dear Indian Ocean.

Sheer poetry Brita. Delighted to experience a different bit of The Indian through your vivid words. I share your love of this magical stretch of blue and would love to do the southern route next time. Of course I’ve still got that one last very big leg to complete to join you in the Atlantic. See you soon.

Thanks Lisa. I have loved your pictures of the northern route too.

One more ocean to go! Look forward to seeing you in January!

Brita, you are such a powerful writer that I worried for your safety with each word I read. I am so grateful you are safe. I can’t even imagine the challenges you welcome into your life. You simply amaze me‼️🙏🏼

I never worried for my safety. There was definitely a moment rounding the cape when I thought, if something goes wrong on the foredeck, I’m not sure we can safely go forward to deal with it. But as long as conditions held and nothing broke, we were completely safe. That was a few hours of tough conditions out of a few months of sailing. Not bad in my book. Sorry if I make you scared. :(

“There is a river in the ocean. In the severest droughts it never fails, and in the mightiest floods it never overflows. Its banks and its bottom are of cold water, while its current is of warm. The Gulf of Mexico is its fountain, and its mouth is in the Arctic Seas. It is the Gulf Stream. There is in the world no other such majestic flow of waters. Its current is more rapid than the Mississippi or the Amazon.”

Matthew Maury

The Physical Geography, 1855

Speed wise, the Agulhas Current is very similar to the Gulf Stream. Weather wise, it is much fiercer, because these low systems keep building off the cape and pounding wind against current.

Thanks for that. I went to Matthew Fontaine Maury Grade School in Memphis. As you probably know, Maury was a naval officer in the mid-nineteenth century. He was the first person to map all the oceans’ currents and prevailing winds. His work was acclaimed by mariners world-wide. His quote about the Gulf Stream is colorful.