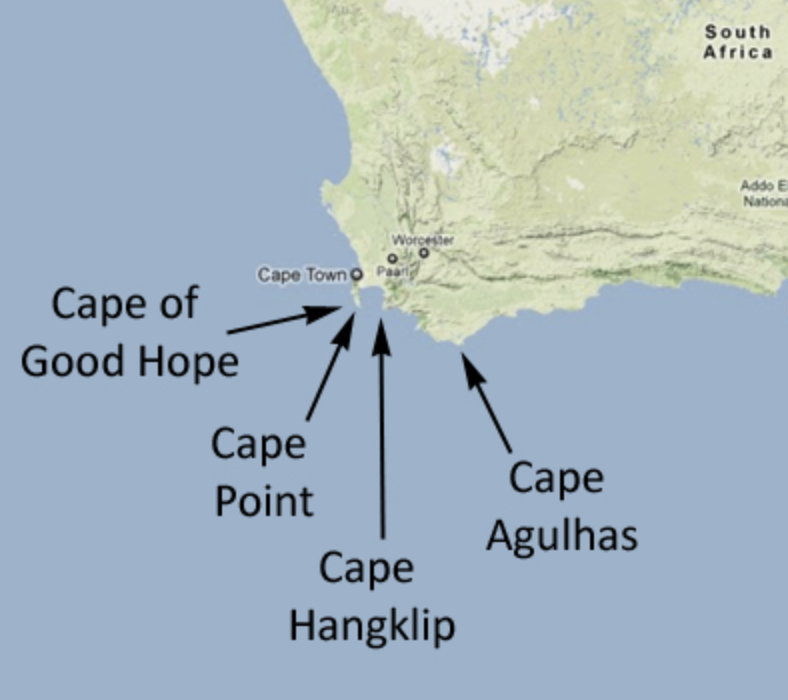

Five hundred years ago, before GPS and AIS, before paper charts and sextants, Portuguese and Dutch sailors were picking their way down the African coast looking for a waterway to the east. Bartolomeu Dias was the first to round the tip of Africa, naming the cape near present-day Cape Town “Cabo das Tormentas” or “Cape of Storms” and the cape 155km southeast of there at the southern most point of Africa “Cabo das Agulhas” or “Cape of Needles”. Cape of Storms was renamed Cape of Good Hope to reflect the hope for prosperity the eastern water route brought. Cape Agulhas kept its name, which refers to the rare coincidence of magnetic north and true north that Portuguese sailors noticed near the cape then.

Rumor has that it the Dutch discovered Cape of Good Hope first and believed it to be the southern most cape of Africa, and most of the world probably thinks the Cape of Good Hope actually is _the_ cape of Africa. It’s not. And if you’ve rounded both under sail, you’d never make that mistake. Cape of Good Hope is like a bathtub after the washing machine of Cape Agulhas. Cape of Good Hope is too far north to experience much of the piling up of winds and currents where the Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean meet further south on the continent. At the real cape – Cape Agulhas – the westerly winds of the Roaring Forties and the easterly Antarctic Circumpolar Current from the Atlantic Ocean bash up against the easterly trade winds and the westerly Agulhas Current from the Indian Ocean, among the shoals of the continental shelf just 100nm south of the cape. These counter forces in the water and in the air make Cape Agulhas as brutal as you’d imagine a true cape to be. When we rounded Cape Agulhas on 28 November 2018, we experienced 40 knots of wind and waves crashing over our bow and into our center cockpit, and we considered ourselves quite lucky. Friends have told stories of 90 knots on the nose and waves pushing them right up on the shoal. Hundreds of ships are wrecked there.

I was so proud of my first cape rounding at Cape Agulhas – maybe as proud as I was when I finished my first ocean crossing in Australia. I posted a blurry picture of Ruud and me drenched and freezing and holding on tight as we rounded Cape Agulhas around midnight. I got some likes, sure, but I am pretty certain 90% of my Facebook and Instagram followers have no idea what Cape Agulhas is or why it’s a big deal. Rather, when I posted a picture of our rounding of Cape of Good Hope led by dolphins, then I got a flood of likes and congrats.

Rounding Cape Agulhas felt like a false summit for me – you work so hard to make it there, and then you reach what you thought was the summit and realize you have so much further to go, or maybe you even reached the summit but no one else perceives it that way. I imagine the Portuguese and Dutch sailors felt the same in reverse – they reached Cape of Good Hope, where they were finally able to turn east after their long southerly haul, but they still had a day or so of sailing before they tackled the real cape at Agulhas.

It’s a false summit either way, and it can be emotionally crippling. I experience it every time I sail back to New York; as soon as I see the Verrazano Bridge spanning the harbor, I feel like I’m home. But I’m still far from home – 6nm to the Battery and 8nm to Chelsea Piers. (And even once you’ve reached what used to be home, will it ever feel like home again? But that’s another story for another day.) I experience it at most island landfalls too; as soon as I round the corner of the island into the leeward side, I feel like I’ve finally reached my destination, but I haven’t, the harbor is usually several miles down the shore far from the winds and waves rounding the headlands. When you’re completing a passage of thousands of miles, a few more miles may not seem like much, but those miles from the headlands’ false summit to the harbor’s real summit can be the longest of the entire passage. When we rounded the northern point of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean after 2370nm of a trying passage, very ready to be reunited with our fleet, the 12nm down the northwest shore to Port Louis were brutal. We had just enough wind for a leisurely sail down the lee shore, but we had not nearly enough patience to go any slower than possible. The engine was in gear and we were making as much headway as we could to the true summit.

After false summiting the southern most cape of Africa, I was mentally preparing myself for the false summit I faced on the highest peak in Africa. On Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, just twenty minutes or so from the summit at Uhuru Peak at 5895m amsl, there is a false summit at Gillman’s Point at 5685m where most hikers stop to rest. My trekking company’s informational brochure (see below) warned that you may want to stop here. Luckily I blew right past it on the way up without even taking a picture, though my guide stopped me on the way down to snap one (thankfully).

“When you reach Gillman’s Point you will sit and rest. At this point the body often thinks you have finished your uphill fight and will be trying to coerce you into giving up and turning around. While you may genuinely believe that you have already exhausted your reserves in reaching this point, this is actually very unlikely to be so. Remember that you are only 187 vertical metres short of the summit (via Stella Point), the journey from here is much less steep, and you have plenty of time for further pauses. If you do feel the need to give up at Gillman’s Point please proceed towards the summit for just two minutes before making your final decision. In most cases this act of re-establishing momentum is enough to persuade the mind and body to co-operate with your intentions and you will ordinarily find hidden reserves for a final push, reserves that you were not aware you still had.” ~ Team Kilimanjaro

The experience reminded me that our false summits and true summits are largely mental. The key is to keep your head down and keep going, to relish every accomplishment for its own worth, to never stop till you get to the top, and to define a new top when you do.

To read more about the relationship between hiking and sailing, check out: What Goes Down Must Come Up.

Wonderful story Brita. It’s amazing how hard it is to be patient in getting to your final goal. Grit is a wonderful quality. Onward. Loren