Sharing a boat is a precarious situation. You are entrusting your life to someone you don’t know very well, in confined quarters, far from help. Captains are inviting strangers into their home and letting those strangers be caretakers of their most precious possession. Crew are living under someone else’s roof, according to someone else’s rules, letting them make critical decisions about their safety and well-being. It takes a tremendous amount of trust and flexibility and cooperation.

When I was faced with the prospect of finding a new boat, I leveraged my network. I asked everyone I knew whether they needed crew or knew anyone who did. When nothing materialized, I had a few trusted friends reach out to their networks. When we had identified a few boats looking for crew, I did my due diligence. I talked to everyone I know who knew the captains and sent friends to check out the boats. I FaceTimed with the captains and sent long questionnaires about the boat, life aboard and the captain. If former crew was available, I grilled them. I used my networking and investigative skills and trusted my gut.

As I prepared to move aboard a boat with a captain and crew mates who I didn’t know well, I put in place redundant exit options. I was prepared to pay for taxis, hotels and flights if I truly feared for my safety. I was prepared to endure an uncomfortable, long passage if our perceptions of ideal sailing conditions or fair divisions of labor didn’t match. I acknowledged my role as a guest in their home, a steward of their boat and an unpaid employee in their adventure, and tried to protect myself to the extent possible in such a circumstance.

Since completing my circumnavigation as crew on boats whose captain and crew I didn’t know particularly well, I have been flooded with questions from female sailors about how I did it, whether I recommend it, and how to stay safe. None of this strikes me as particular to being a female. Most captains and crew are men, and a male captain or crew might sexually harass or sexually assault a female crew, but that strikes me as a reality of life, not a risk particular to crewing sailboats with strangers.

In my fifteen months as a crew member, I sailed with one captain I didn’t know well, one captain I didn’t know at all, and seven male crew mates I didn’t know at all. I was blessed by very caring and capable captains; their wives were aboard all the time or as much as possible. I admired and trusted most of my fellow male crew mates. I am not sharing any horror stories because I don’t have any to share.

Here is the best advice I can offer to a woman looking to crew for an unknown captain.

(1)Use your network. Reach out to every sailor you trust to see if they know any captains looking for crew. Check with the commodore and instructors of your club. Post on social media, especially forums like Women Who Sail or your local sailing Facebook group. If you can’t get to know the captain and crew before you get on board, rely on the judgment of people you trust. If you have a problem on board, alert your network so that the captain or crew can’t keep acting badly.

(2)Use Websites Wisely. Here is the closest thing I have to a horror story. I’ve never done online dating; I don’t even talk to strangers; but I was desperate to find a boat, so I put up a profile on FindaCrew. I was very specific that I didn’t want single male captains or any romantic or sexual relationships. As soon as my profile posted, my inbox was flooded by inquiries from single male captains looking for a young single woman. One sent pictures of himself in a white speedo. My profile was down in less than 24 hours, and I will never expose myself in that way again. But one of the women who swapped boats with me across the Pacific Ocean had met our captain and his wife on a crew finding site, and another friend found her current captain and partner through a website. So, if you can stomach unwanted solicitations, get on a crew finding website, wade through the muck and see what surfaces. There are thousands of opportunities out there. For those of you looking, here is a list of crew finding sources put together by my friend Lisa, the woman who convinced me that crewing across an ocean was possible.

(3)Do your homework. Write a list of your own requirements regarding boat maintenance, safety gear, and life aboard, and ensure that the captain and the boat meet those requirements. If you don’t know what to ask about, look at articles in sailing magazines about safety best practices. Search the internet for any horror stories. Grill the captain and former crew about maintenance or relationship problems.

(4)Trust your gut. If something doesn’t feel right at the dock, it’s not going to feel any better mid-ocean. If you have real concerns about the boat or the captain, those concerns will plague you offshore, whether they give rise to problems or not. And if your concerns do come to fruition, you won’t have much protection from it out on the water. Don’t get on the boat if it doesn’t feel right. There will be other opportunities. Be sure to couch your declination as respectfully and blandly as possible, because sound travels very well over water.

(5) Pick wisely. Look for couples or families. Look for boats that have had other female crew. Look for female captains. Look for captains who have had repeat crew. Join rallies where help is just a radio call away and a new opportunity is tied up down the dock. Finally, look for captains with careers or lives that would grow personal skills that matter to you – good fathers, corporate executives, religious commitment, etc.

(6)Test the waters. Spend some time aboard before you cast off bowlines if you can. Start with a short sail if possible. Take the captain out for drinks to see if he drinks too much or comes too close. Don’t step onboard a boat crossing an ocean with a captain you’ve never met, and expect not to have any issues.

(7)Be prepared to bail and bail fast. Have the financial resources to get yourself off the boat. Know where you can go to get help. If you’re not comfortable onboard, make a change as soon as you get to port. I met women mid-ocean who were uncomfortable on their boats and desperate to find new boats to sail off in. Finding a good captain and boat mid-ocean is not a back-up plan; get a taxi, find a hotel, and take a plane. Underway, try to distance yourself from the situation (keep calm and sail on, stay in your cabin as much as possible, use other crew as a buffer) and wait until shore to raise all but life and death issues.

(8)Be honest with yourself. Sailing is an unpredictable sport and therefore inherently involves risk. If you are terrified to sail, don’t blame the captain. If you inherently don’t trust men, don’t get on a sailboat with a male captain. Mid-ocean is not the time or place to overcome fears or prejudices.

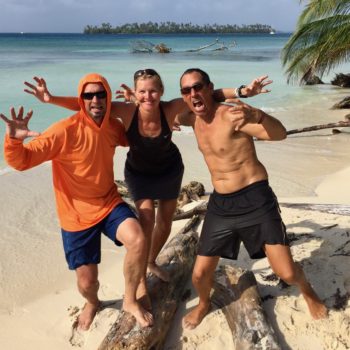

So blessed to have crewed on

Amara with Rick and Brenda and on Blue Pearl with Ruud and Laurie.

Use your network, do your homework, be prepared to bail, and stay safe, sailors.

Fantastic insights Brita! Wish I’d had access to this wealth of knowledge when I started chasing my sailing dream. Delighted to have helped you see your ‘possible’. You are unstoppable once you put your mind to something. Hugs to you from Brazil. Looking forward to seeing you back in NYC at some point and/or on the high-seas.

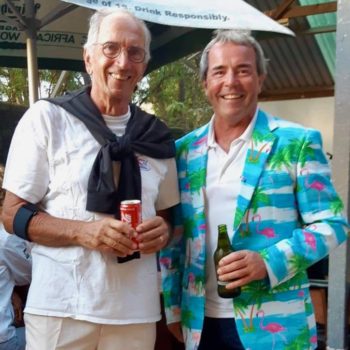

PS – Your joie de vivre jumps out of every picture …and Rob looks great in that jacket.

Great post with such practical advice! I’m into it. Thanks for sharing Brita!